|

|---|

How to sit 7 "Eat two parts out of three" (Adult Practice XXVII) |

We had a look at the sesshin schedule at Antaiji last month. The new schedule consists of fifteen 45 minute periods of zazen, 12 sets of 15 minute walking kinhin, two meals and two breaks after each meal. When people hear that we sit one period more than before, and have one meal less, they might at first think that the schedule has become even harder than it used to be. But actually the opposite is the case. In the old schedule, most periods were 50 minutes long, and the periods after each meal lasted even for one hour. This made sitting a hell, especially after lunch, from 1 pm to 2 pm, and after dinner, from 7 pm to 8 pm, unless you were one of those blessed ones who would just sleep through these periods. Sitting for 5 minutes less makes a big difference, and the 15 minutes less after each meal make it possible for some people to sit through the new Antaiji style sesshin who could not handle the old schedule. Also, especially for Japanese "two meals a day" sounds very ascetic, but in the midst of sesshin, you usually don't feel so incredibly hungry. Quite contrary, the more you eat the more pain you will experience. So reducing the meals to two meals a day helped to reduce the pain in the legs too, and no-one who sat with the new schedule at Antaiji has been starving, rather most people expressed satisfaction with the changes. So my main reason for changing the schedule was not to make it stricter, but less painful and physically exhausting, both by cutting the sittings a little shorter and by having only two meals a day, which is just enough. Again we might want to add here that it is ideal to have slept well before zazen and not to be too exhausted, but - especially in a monastic environment where you can never choose if you want to sit or work or stand in the kitchen or rest - it will happen often that you do not get all the rest you want and feel very exhausted indeed. Then again, this will be an opportunity to practice patience and perseverance on the cushion. Actually, I think that this point is very important when we think about the problem of falling asleep during zazen, which is a very common and serious problem for many practioners here in Japan. I said before that it is vital for anyone who has this problem that they first of all realize that they are actually sleeping - when they sleep, they don't know it, and when they wake up, they don't realize that they had been sleeping all the time. Next, it is important to realize that it is me who is sleeping. No-one else is responsible for that. We must not blame it on the environment or the fact that people didn't let us sleep last night or that we had too much work to do the last couple of days. The self-sufficient life here at Antaiji involves a lot of work, and the work that I don't do now will have to be done by the others. Therefore it is not good when I say: "Sesshin starts tomorrow and I really don't see why I have to do this job here right now - I'm soooooo sick and tired of it!" But that doesn't mean that we don't get any rest at all. Actually, if we use the 24 hours of our time in an intelligent way, we will find that we get all the rest we need. The question is only: do we really use the time in an intelligent way? Do we use the time that we consider our "private time" (but there is really no time that can be called private) or "free time" (but all the time of your life is FREE TIME, isn't it? Or what did you think that practice is!?) to prepare ourselves for zazen, or do we just "kill" that time? If we do kill it, we are killing zazen with it. By the way, too many people who come to Antaiji complain that they have "no time " here. At Antaiji, we have 24 hours each day, just as everyone else in the world. It is just that we sometimes start to think that when we work or stand in the kitchen, or even when we sit in zazen on the cushion, that this time is not "our time". But if that time is not our time, who's time is it? The problem seems not to be that we have no time, but rather that we don't know how to use time fully as our time, i.e. to commit ourselves completely to each single moment of life. In the "Tenzo-kyôkun", Dôgen Zenji says that without bodhimind your practice will only exhaust yourself without any merit. What is bodhimind? In the same "Tenzo-kyôkun", you find the response: "To roll up one's sleevs and work is called bodhimind". And in the "Gakudôyôjinshû", Dôgen Zenji makes the point that if you try to have it easy, you will be miserable even when you lie down to have a nap. So when we feel sick and tired of it all, is it really because we are working so hard, or is just that we are lacking bodhimind? Or maybe we have just forgotten that all 24 hours of the day belong to us, they are our practice!? There are limits to physical exhaustion though, and if fatigue becomes a chronic problem, sleeping during zazen can turn into a habit which once acquired is difficult to get rid off again. When I first came to Antaiji, the monks said that "the sesshins are our only holidays". That was true in so far as sesshin were the only time were you could just sit and relax, recovering from the endless work in between the sesshins. Often work was so intense on the normal days that the monks didn't really feel like eating after samu - you were just too exhausted and tense. That led to the paradoxical situation that we ate more at the meals during sesshin than we would normally do after work. As the tenzo (temple cook) would not participate in the zazen, he had the whole day from 4 am to 9 pm to prepare food and was expected to serve one or two dishes more at each meal than on a regular work day, that means rice and soup and three side dishes. Therefore sesshin were considered by some to be a culinary feast. "What fun is there during sesshin except eating and sleeping?", they would say. And after the sesshin: "Wow, the tenzo did a really great job this sesshin, I gained 2 kilos in three days!" It goes without saying that sesshin are not meant to be culinary feasts. Of course it is the tenzo's job to offer delicious food to the sangha. But he also has to consider the occasion, and a meal during sesshin requires different food than a meal on a work day. Keizan's advice to "eat two parts out of three" is very wise. You just can not sit with a full stomach. One more cause that led me to change the sesshin schedule to two meals per day was the fact that after the funeral of the former abbot, all of my dharma brothers left Antaiji, and for the first year I was alone with only one more lay practioner who had arrived just after the funeral. That means that I had to be the tenzo, strike the bell in the meditation hall, and be the work leader at the same time. Of course that is impossible. So to enable me to be present in the meditation hall and at work, but also to get cooking done in the kitchen, I first bought an electrical rice cooker (before we used a pressure cooking pot on the wood stove) and a micro wave. Without the rice cooker, the tenzo would have to start the fire in the kitchen two hours before the meal, but now you just put the rice and the water in the machine, set the time, and it will be ready for the meal automatically. The micro wave on the other hand made it possible to prepare all the side dishes for the sesshin on the free day before sesshin in advance. So during my first year as the abbot, I would ring the kinhin bell before a meal, get up and go to the kitchen and prepare all the food (rice and two side dishes) during the 15 minutes of kinhin. On the work days, me and the other practioner would work together until half an hour before a meal, and then prepare the food together in the kitchen. Only thus it was possible to keep up the work schedule and do all the necessary cooking at the same time. Only during my second year as the abbot was it possible to switch back to the rotation system, where one monk is the tenzo for three days, and doesn't have to participate in work or zazen on those days. Only during sesshin, because there are only two meals to be prepared now, the tenzo can sit for about 8 or 9 out of 15 periods together with the others.

to be continued ... (Docho)

|

|---|

|

What Ordination means to me |

Ordination or tokudo means to enter the way of Buddha or following the

path of Buddha. People who get the robe and the Kesa joining the Sangha

and left home, living in the woods or in a monastery. Today especially in

Europa or America most people taking tokudo don't go to the woods but

live at home, taking responsability for their families or job. So, the

question is how to create an ordained way of life in a normal context.

One can think about the kai (precepts), the praxis of zazen and so one, maybe the

essence is on another level; it is not prior in which concrete

circumstance but in which manner one lives. I can be aware of what I'm

doing or not, I can orientate towards personal belongings or on a

reciprocally sight of life. On the other side it's clear that this does not depend on being ordained or not. So, there is also the formal side, to make it obvious for others that I'm living my life orientated on the following the path of Buddha, and second, for me more important, a kind of inside, a encouragement of my one and for my practise. And it's the third step for me, first to meet zazen-practise in Berlin 1979 and following these way up to the second step, my lay-ordination by Taiten Guareschi 1983. He gave me the name Shinryu, true dragon, which I like very much because its poetic and the story behind is funny. There was a guy drawing dragons many years and a real dragon heard about that and thought, that this man must love dragons very well. So he decided to visit this man, but when the dragon looked through the window and the man saw him, he was very anxious and hid under the table. The true dragon is our own real nature, our Buddha nature, and so the story encourage us not to be afraid when we realise our true nature. The third step was my ordination as a monk in June by Docho-san which I received with a sense of pleasure and deep thankfulness, and I will see in future how I can creating an ordained life in everyday life. Maybe I can realise the true dragen maybe I creat a frog! Both would be fine, I like frogs very much. They helped me to sleep in Antaiji where they were loud as an orchestra. Maybe the best answer of what being ordained means to me is: "I don't know..." I will expand this topic (sorry, but only in German) on http://www.sotozen.de .

(Shinryu)

|

|---|

|

2 in 1 |

Four weeks into my stay, I would like to share my impressions of practice at Antaiji. As you read my input, please keep in mind that this is my very first vist to Japan but that I have previous experience from being a long-term guest at Buddhist monasteries. Ever worked barefoot in a rice-field with mud up to your knees? The water gets nice and warm round midday, perhaps that's why you're never in there alone - the frogs love it too! Work (samu) at Antaiji is often physically demanding. There are many types of jobs around the nearly self-sufficient establishment, which makes for variation. With high air humidity, working under the frying sun can be quite demanding; however, I find that the samu strengthens my overall endurance - which comes in handy during sesshins. Antaiji is set in a stunning mountain-landscape and it is as exotic as it is tranquil. The main meditaion hall (hondô) is the heart of Antaiji with its flared roof and atmospheric interior. It's very spacious and the floor is covered with traditional straw-mats (tatami). The sesshins are tough, as in long hours of sitting meditation (zazen) and walking meditation (kinhin). Allow the samu and the sesshins to strengthen your endurance, and say to yourself, "I'll never give up". For one, my stay at Antaiji has made me a fighter; even though the samu is beating me to death and my body is achiing badly during the sesshins - I have learbt to stick it out. Endurance can not be bought in a can, it must be cultivated. With the right attitude, Antaiji becomes a place for transformation; resisiting the samu and the sesshins will only make things worse, accepting them for what they are - make you flow. How would your life change for the better if you had access to more inner strength (endurance)? For me, Antaiji is both hard practice and great fun. With a young abbot, you can't go wrong; how about a camp-fire under the stars or a day at the beach, with norkling and packed-lunches? I could not imagine a stay at Antaiji without the exchange of experiences with my fellow practioners. Thank you for reading my input. Kindness is happiness.

(Axel)

|

|---|

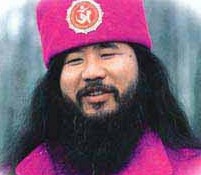

"We can't do anything." (Part 4) |

Who is to be held responsible for the Salin attack in the Tokyo subway ten years ago? No-one but the Aum cult itself of course. On the other hand, many Buddhists excuse themselves by saying that this cult is only pseudo-Buddhist and that the attack therefore has nothing to do with them. But this is not true. It goes without saying that there is nothing "Buddhist" about the attack. But this event, just as any other event, can not be singled out from its wider context, and the Buddhist community, especially the Japanese Buddhist community, is part of this context. I was impressed by the honesty of the Rinzai and Ôbaku officials, who called the attack not just a problem on the side of the Aum cult, but "our problem", and even went so far to say that if we do not solve this problem, a second or third attack of this kind might occur any time. So what answer do the officials give to their own question: "What can we do?" Quite surprisingly, their answer is: "We can't do anything." At the beginning of their symposium, the discussion had still focused on concrete questions like what monastery could take how many refugee Aum believers and how food and bedding could be provided for those refugees who's numbers might go into the hundreds. The officials learned quite soon though that there was no news of any Aum followers having asked for help or asylum at any Zen monastery. No-one on the side of the disappointed Aum believers seemed to expect the Zen priests to do anything. And on the side of the Zen priests it also seemed to be no-one but the officials in the sect's headquarters who asked themselves: "What can we do now?" On the level of the single family temples, which account for 99% of the Zen sect, no-one ever was interested in the problem posed by Aum. Even though the incident might be mentioned during the conversation of the priest with the parishioners after a funeral ceremony, neither the priest nor the parishioners would treat the topic as a religious or Buddhist one, not to speak of thinking of it as their "own problem". Aum was just another social event that produced gossip, and not much more. So no-one basically expected the Zen Budddhists to do anything - no-one in Japanese society in general, where Buddhism is considered to be just another way to make easy moeny, nor the Aum followers, who never trusted the Buddhist establishment in the first place, nor the Buddhist clerics themselves, because they are busy performing funerals. The questions remains then why the officials at the top of the sect would talk so much about Aum being "our problem", if nothing of that concern is shared by the individual priests in local or city temples. How come that the consciousness inside the Zen sect is so divided? Let's search for some reasons next month.

to be continued ... (Muho)

|

|---|