|

|---|

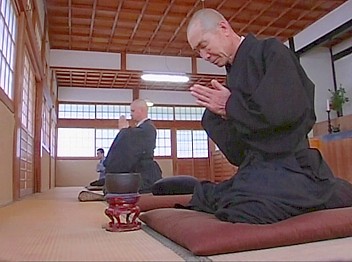

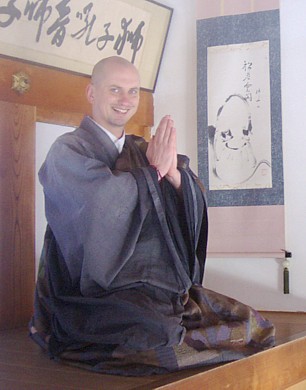

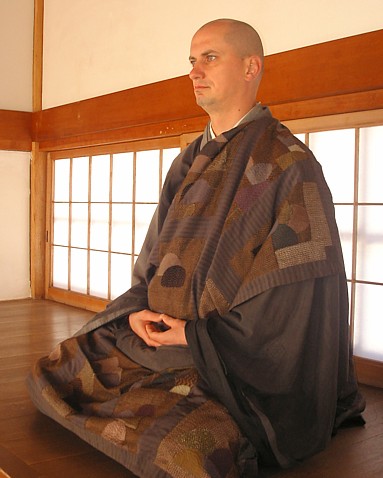

Why bow to a cushion!? How to sit (Part 14) (Adult practice XXXIV) | The following instructions for zazen are translated directly from "Zendan". They are about preparing and approaching the place for zazen. Preparing the place where you sit 1) Enter the space where you sit with a respectful mind. 2) Spread a square mat (zaniku or zafuton) and place a round cushion (zafu) on top. The cushion is about 50 cm in diameter and stuffed with kapok. If you have no such cushion, you can also replace it by a square mat that you fold into two or four. 3) When doing zazen, never lean againts the wall or a chair. 4) The quality of your zazen will be very much influenced by the height of your cushion and the way you sit on it.  Starting with zazen When you enter the room for zazen (dojo), first bow in gassho towards the buddha statue or the scroll hanging in the center. Next, go to your place and bow again in gassho towards it. In a big dojo or sodo (training monastery), someone will teach you the rules. When many people sit together, there are two different ways to sit: Facing each other and facing the wall. For beginners, facing the wall is better.  ഀ ഀഀThese instructions can not be found in the book "Shikantaza", and they are onbviously meant for Japanese lay practioners who have never been to a major dojo. Most people in the West who practice zazen will have their own zafu. Japanese Rinzai monks don't use the zafu but fold their zafuton - which is about two meters long! - but I think even many Western Rinzai practioners today use a Soto-style zafu. It is just much easier to use, although I myself remember sitting for the first three or four years on a blanket that I folded up to the right height. ഀSawaki Roshi mentions not leaning against a chair. He does not say if sitting on a chair is out of the question at all. I think there are practioners in the West who just have no other choice. They can not sit on the cushion, at least not for long hours. Still, even when you use a chair, you should not lean against the back of it. It will be best to use a chair without a back. Also, even though you might choose to sit on a chair, be prepared to experience pain. Some way or the other, you will suffer (even if you don't do zazen you'll suffer). In another text, Sawaki compares the zafu to the sword of a samurai - it is essential for your practice of zazen that you know how to use it and that you choose one that fits your body. It is a little confusing that Sawaki mentions both Rinzai-style sitting facing each other, and Soto-style sitting facing the wall. If you sit with a group of people, forget about which is better for beginners and which is better for advanced practioners and just folllow the rules of the group. In most places, you won't be asked for your preferences anyway. Historically, there was only sitting facing the wall until Hakuin changed it to sitting facing each other. This style of sitting is probably practiced only in Japanese Rinzai Zen, you don't find it in Korea or China. It helps you keep focues in the present, and it helps the jikido (the guy who goes around with the stick and beats people) to see if you are sleeping or are in some other kind of altered state of conciousness. ഀSawaki mentions bowing towards the cushion only, but usually you will turn clockwards after that and bow a second time, facing the room. In many dojos, if you sit first and the guy sitting to your left or right comes later, you will respond to his bow with gassho. So you bow at least three or four times before you can start with zazen.  ഀOne question that some Westerners might ask is: Why do I have to bow all the time? Why do I bow to a wooden statue of the buddha? Why do I bow to the cushion? Why bow to that wooden plate in front of the toilet with the Chinese characters I can't even read? Why bow before and after entering the bath? Why the hell do I have to bow at all? I remember reading a book by van de Wetering in my youth, in which he says that Zen monks bow to their cushions because one day they will reach satori on them. At the time, I thought that that must be the reason of their bows: The hope to be rewarded for zazen by satori, like a dog swaying his tail in hope for some peace of meat. Today I can only smile. ഀIn last year's april issue of the "Lotus in the Fire", I quoted the words of Okumura Shohaku Roshi that hint at an answer: "A candle, flowers, and incense are offered to create a sacred and peaceful atmosphere. When we sit, the space is also practicing zazen with us. Our zazen and the place we sit are one. The same is true of our lives and our environment." ഀഀOkumura Roshi doesn't speak about bowing here, but he explains the importance of the space we sit, practice and live in. Or, to be more precise, we do not live in the space, we live the space. That is why we pay respect towards the space, even the zafu which we sit on. Of course we also pay respect towards the buddha, without whom we wouldn't have the chance to meet the way and practice the dharma today. We also pay respect to our fellow dharma members, out of gratitude for walking the path with us.ഀ ഀ  ഀ ഀഀStill, one might ask, why do I have to bow to pay my respects? Isn't it enough to just be grateful in one's heart, and behave natural? One could just ask back: Why not bow with hands in gassho and lowering one's head? In the past, there were Westerners who refused to bow or kneel before the Chinese emperor, even at the risk of decaptivation. Why? Because we know that kneeling down, doing a prostartion or even simply lowering one's head means giving up one's ego. And we somehow feel a resistance against that. We don't want to bow, because we don't want to give up our ego. ഀSawaki Roshi said once: "Try to have a fight with your spouse while you have your hands in gassho - you won't be able to do it!" ഀWhen we put our palms together in gassho, something in our bodies absorbs everything else - the ego with its endless claims doesn't appear at the surface anymore. Therefore we bow before we sit, or eat, or even just want to have a pee in the toilet. To pay respect to the space, our fellow practioners who live the same space, and let go of our egos. Bowing is exactly not swaying one's tail.  ഀAnother thing important to keep in mind is what I already said about the meaning of the o-kesa: Things have only as much meaning as you give them. If you bow while your mind is somewhere else, you will ask yourself sooner or later "why do I bow?" Gassho won't be real gassho. Your fingers aren't touching each other properly, the hands aren't pointing upwards anymore. Not only you will be asking yourself what you are doing there, others won't see a mind of respect and gratitude manifest in your bow either. But even if you are bowing according to the manual, going through all the movements like everyone else - if you are not inside the action, whatever you do will be meaningless. If your bowing on the other hand is done wholeheartedly, it can't be but meaningful - or rather: The question if it is "meaningful" or not won't appear in the first place. You and the bowing are one, the bowing has to do the bowing. So, bowing is not just a preparation for zazen - when you are bowing, you are already practicing the zazen which is good for nothing. (to be continued ... Docho) |

|---|

|

ഀ Letter from a Novice Monk – Part 3 Just do the best you can | In my last letter I wrote about my current working life. Working as a “psychotherapist” I get to see people who make appointments to come and see me. They see me for free, and (maybe in part because of this) it is not uncommon that an appointment gets made but then the person does not show up. I do not mind when this happens and use the hour to catch up on paperwork or sit zazen in the empty consulting room. If and when I get to see the same person again, often they apologise by saying something like “sorry but I forgot about the appointment” or “sorry I couldn’t make it because of (x,y,z)”. It occurs to me that as practitioners of Zen we all have current and ongoing appointments with our practice in the here and now. For me as a monk this is my life. Yet if anything, I now seem to be only more aware of where and how I routinely miss many of my appointments with my own life in the way it is. Obviously it is up to me, and not anyone else, to keep my appointments, or not to keep them, or to apologise if I don’t keep them.ഀ ഀI have no apologies. My appointments with my life are perfectly free, as they are for all of us. This point is also made by Docho-san when he writes that there is actually no difference between our practice and our “free time” (except in our heads). Yet the splitting between the present as it is and something other that is supposedly better does not simply cease because we decide that it should. As with all habits of the mind it has its own momentum, and at best we have the choice of witnessing it rather than being driven by it. Of course one reason why this simple choice is not an easy one to practice is that the reality of our present moment mostly seems lacking, disappointing, or too harsh in some way. Whenever I’m actually awake during zazen, I usually become aware of my resistance and tension which arises from this, and of my instinctive wish to obtain relief from it. While it’s always possible to “miss the appointment” and simply not be here, the reality is that it’s nevertheless the only appointment we have.ഀ ഀWhen I was at Antaiji a few months ago, or maybe shortly afterwards, I was fortunate to have had my head turned in a way that is helpful to make us see our own footsteps (or shit in the toilet). In this instance it has brought me face my own peculiar resistance to the reality of my life as being not so much to do with choosing to resist as with resisting to choose. But having no choice between different appointments does not mean one need not actively choose the appointments that one has. Many times in Zen I’ve heard and read different people give the instruction: “Just do the best you can”. I now realize that I have misunderstood it every time. It actually says: “Just do the best you can”. (Gassho, Seikan) |

|---|

ഀ Oh Lord, want you buy me... A Mercedes Benz protected by a kesa from the dust of the mundane world in a Wat in Bangkok. | ഀ

ഀ

ഀ ഀOn March 30th, we still have about one meter of snow. When will White Christmas ever end?ഀ | Everybody in Antaiji is waiting for the carrots that were buried under the snow at the beginning of December. I will continue to write about Aum and Japanese Buddhism in July.  (Muho) |

|---|