Lotus in the fire

A Zen master and inemuri zazen (Adult practice - Part 48) |

Let us take a short break from studying the details of a Japanese Soto-shu monk's career. I would like to quote from a newsletter that just arrived from Itabashi Zenji's temple, Gotanjoji. Gotanjoji is one of thirty-something official Soto training monasteries, and Itabashi is only one of (I think) three living persons who have the title of zenji. Zenji literally means "zen master". There are some who say that there is no such thing as a Zen master (because you do not master Zen), others claim that Dharma transmission or Inka or whatever document they picked up un their spiritual travels qualifies them as an officially acknowledged Zen master. Others try to combine both claims and say: There are no Zen masters, but if there are, than I am one!

Anyway, Itabashi Zenji writes in his newsletter:

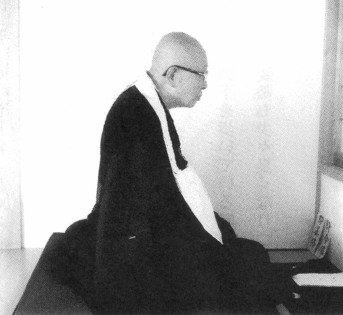

"I always had a bad posture since I was young. I am stooping a little, with my head hanging forward. I tried to FIX that for a long time. But nothing seems to help. So I thought that maybe I inherited from my mother, "it must be in the genes", I said.

Especially my posture during zazen is bad. ... I also do a lot of inemuri during zazen. Also, maybe because of my bad posture, I have a lot of random thoughts and delusions rising up during zazen without end.

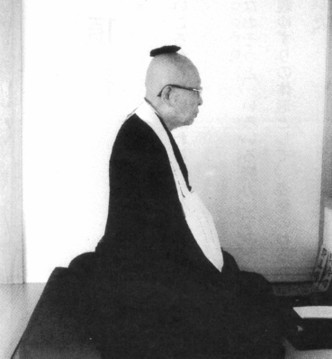

... Several times I asked the monk who walks around with the kyosaku stick to correct my posture and wake me up from INEMURI by beating me really hard. But for some reason he ignores this old monk. And not only that: One of the monks even took a picture of my inemuri zazen and presented it to me!

Already 60 years have passed since I started zazen as astudent in Sendai. I had almost given up hope, thinking to myself: "Now look at what kind of monk you became!"

But recently, I had a good idea! I started to put a small cushion on my head during zazen. And it had the result I was hoping for: Whenever i start to do inemuri, the cushion drops from my head and I wake up. It sometimes happens that the cushions drops ten times during one period of zazen. Especially during the second period in the morning.

Also, since I started putting that cushion on my head, my posture has improved so much that I can realize it myself. My spine seems to be erect, directly connecting my sitting bone to the top of the skull. My hips are rooted, and I naturally start to breath from the abdomen..."

I think there are lots of things we can learn from this newsletter. About the humbleness of a true Zen master, for example. But also about the meaning of zazen kufu, one of the two aspects of Zen practice that Dogen Zenji mentions at the end of the Gakudoyojinshu (the other aspect is sanshi monpo, i.e. to meet with a teacher and ask about the dharma). Zazen kufu means to try one's best at zazen. "trying one's best" here implies experimenting, trying various ways, giving one's all, never giving up.

I commented about the problem of inemuri zazen in the past. Also here at Antaiji, sleeping during zazen is a big problem for some of the monks. It seems to be a greater problem for the Japanese part of the sangha, but westerners also sometimes sleep during zazen (usually it is the Westerners though who say: "I can not concentrate on my zazen because my neighbor sleeps all the time"). My own experience with this can be found in the "adult practice" series, starting with part 7 (continuing until part 12). About the difefrence of the Japanese physical experience of zazen in comparison to that of a Westerner, see part22.

Still, I never saw anyone do the kind of kufu Itabashi Zenji does in his old age. Respect!

This is all for this autumn, but below you find four essays by Brendan, who has been living here since June.

[Muho]

Thank you for indulging my heretical thoughts. I only hope that these at least are stimulating and encouraging for people, whatever their path.

Essay 1: The Near Enemies and Friendly Neighbors of Shikantaza

Shikantaza practice has many near enemies and many friendly neighbors which a yogi inevitably runs into as they practice. I'm not giving a precise map of the neighborhood, nor the name of the annoying dog that sometimes barks and shits on your lawn, but just the ones I find to be most helpful to be alert of in practice. I'm going to talk about its two near enemies, non-discriminating dullness and discriminating alertness, and its three friendly neighbors of shikantaza, breath, mantra, and intention.

The Near Enemies of Shikantaza:

Non-discriminating dullness. In non-discriminating dullness, although I no longer identify each experience as this thing or that thing, I instead sink into a peaceful, drowsy haze. This is not "just precisely sitting," this is checking out, turning off, and tuning out. Not much different from watching Looney Tunes for a few hours after work except in this case I'd face a wall and be in some fancy yogic posture that makes what I'm doing look spiritual. If I want to awaken to this, to my life just as it is, this practice is not the way. If I want to snooze for a few hours and feel spiritual, this practice is the way.

Non-discriminating dullness does work, but it does so on a slow, superficial level. By lazily sitting and watching all our thoughts and dreams pass by with few distractions, a yogi can observe the three marks of existence (impermanence, suffering, and no-self) which leads to liberation. In my experience, though, these insights remain superficial and psychological and are not of the penetrating sort that cause yogis to give up the fundamental and painful grasping of conditioned phenomena which causes so much of our suffering and the continued sense of separateness from our experience, from this.

Mahayana Buddhist thought attempts to one-up the Theravadan teachings by talking about this profound truth of emptiness, or sunyata, which those silly Theravadan's missed, but, in my experience, emptiness is just another way of talking about the third mark of existence, no-self, or that nothing has any existence independent of anything else.

Discriminating alertness. Opposite non-discriminating dullness, I find I can easily fall into a vippassana-esque meditation style in which my mind jumps after each thought and sensation. I fall into this style more easily with the eyes closed then open and can quickly tell when I'm doing it because my eyes jump around like crazy identifying all the particular experiences that constitute this. When practicing discriminating alertness, though, I constantly separate my experiences - "Now I'm feeling pain in this part of my leg, oh, now that part, and now I'm hearing a bird and now I'm thinking about what could've been with that girl back in California," etc., etc.

In traditional Theravadan practice and in some Mahayana schools, especially with all the mixing that's been going on as Buddhist practice becomes more popularized in America and Europe, they call this mindfulness training, or, the term I like better, frames of reference. In shikantaza, though, we have nothing whatsoever to grasp a hold to, nothing whatsoever to reference back to. In shikantaza, we open up to the totality and immanence of this.

I can also tell when I'm practicing discriminating alertness because it feels as if my attention flickers between the body and all the sensations of the environment around me. In shikantaza, no flickering occurs. This practice, unlike non-discriminating dullness, has great potential. In fact, Mahasi Sayadaw developed an entire meditation system which takes a yogi through all four stages of the Theravadan enlightenment model using something very similar to this vipassana style practice, but whatever it is, it ain't shikantaza.

We do not need to look around or bring our awareness to anything to find a sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, or thought. It's not around the corner, in my pocket, or on the tip of my nose, although sometimes I am damn certain that these sensations are always "somewhere else" and that I have to go there looking for them. It's right here, right now. It's the clock clicking about in the kitchen ten meters away. It's the itch on the bottom of my right foot. Each moment we experience something and all that we need to do is be alert, to open our eyes without looking and we will see this arise and pass away before us. If we were not experiencing a sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, or thought this instant, we would cease to exist. So, why bother looking anywhere or running off to find some sight or sound, just open your eyes. This brings me to what shikantaza is. Shikantaza is...

Non-discriminating alertness. Allowing every sensation which constitutes our existence to arise and pass away within a bright field of awareness without us grasping after it, pushing it away, or sticking a price tag and label on it. Somewhere I heard it described as "alert, non-selective attention to whatever arises in and vanishes from consciousness," which is the best description I've heard so far. Shikantaza is opening your eyes, ears, nose, mouth, tongue, body and mind and has nothing to do with lying, sitting, standing, or walking. It neither begins nor ends on the cushion. It is the single practice of a lifetime.

I'll write more on shikantaza in another article, but this short, simple description should suffice for now.

The Friendly Neighbors of Shikantaza:

Now, in addition to those lazy and sloppy or uptight jerks that live down the street and sometimes invite themselves into our homes on the weekend, we have three friendly folks that help us in our day-to-day practice. The first is the breath.

Breath. Although we focus on nothing and expand all of our awareness to include the onrush of this, it helps to ground that awareness into the breath. In Mahasi Sayadaw's meditation system, one which I think provides a good foil for shikantaza practice, he recommends that in addition to maintaining a wide open awareness to all that occurs moment by moment, we should also bring some attention to the breath. This advice works for shikantaza as well and, since we should, when practicing shikantaza, maintain an alert and wide open awareness of every experience that constitutes our existence, this will inevitably include the breath once shikantaza settles.

There are two paths that a yogi can take towards the breath. The first path is the path of no-path. Sit there alert and focused, attentive to every sight, sound, smell, taste, touch and thought which arises and passes away and eventually you'll find the breath. This method can take too long. There have been times when I have literally sat all day and not found the breath. During these sits, I might find my travel plans, stumble across some interesting, or, more-likely, not-so-interesting, memories, and maybe a few thoughts and painful sensations in my knees and back but little else. During these sits, I chose to run around in my head for a few hours. That certainly can be interesting, and I have heard people report all types of wonderful experiences and visions while running about in their skull, but this is not shikantaza. Shikantaza means letting go of everything. Non-thinking. Neither shooing away nor grasping after any thoughts or sensations. When talking about the awakening of an Arhat, for example, the suttas simply describe the experience as such:

"With release, there is the knowledge, 'Released.'"

No comment on what is released. Not even, as it's sometimes translated, "It is released." There's no noun, no pronoun, just a past participle: "released." That's all, but it's enough.

The practice of shikantaza is a practice of release. If we are not letting go, then we are no longer practicing shikantaza. That being said, it helps to grasp a little bit at first to the breath. By lightly bringing the breath into awareness without focusing too tightly on it, I can easily settle into shikantaza and actually begin the practice of awakening, of release, of this, of sincerely doing nothing instead of just talking about it. If I start to focus on the breath, I just notice it and the onrush of this, the sound of the washing machines clanking about or the birds trilling in the pines, greets me. No one "releases" the breath. By simply being alert to this, we see and experience that there never was a single thing to hold onto in the first place. The breath consists of but one experience of a near infinite number of experiences which constitute our existence. When we notice these other experiences which always are, and always were, occurring and entering into our awareness, then the breath falls away as an object of attachment and becomes one of the many sensations rushing onwards.

If I start to sink into a dhyana samadhi and sense-input ceases, I definitely am no longer sitting shikantaza and have begun to focus on or follow something - my breath, the snores of my neighbor, the pulse of blood in my hand, something. This has yet to be much of a problem for me, and I should only be so fortunate if the greatest difficulty in shikantaza was that I kept falling into samadhi on accident!

Mantra. This second friendly neighbor might sound a bit strange, but repeating to myself a mantra throughout a sit has been incredibly helpful in encouraging diligence and alertness throughout. I find it easy to slip into a non-discriminating, drowsy haze, especially when I sitting early in the morning or late in the evenings. There have been many-a forty-five minutes which I have spent thinking about old girlfriends, planning breakfast as Tenzo, or thinking of what I should have said or should have done. Lately, I have been repeating to myself, "Alert," although this mantra changes with some frequency. I have also repeated to myself, "As if face-to-face with a swordsman in a duel to the death" (Thanks for this one Hakuun Yasutani!), "Wholeheartedly sitting," and "Just sitting," among others. By repeating a mantra, I find that I can again bring back the energetic alertness so essential to shikantaza and I can get myself unstuck from wherever I'm at and whatever I'm doing and open my eyes again.

Mantra repetition also helps kick-start a sit. When my shikantaza settles after an hour or two, that attentiveness and energy sustains itself and the mantra becomes unnecessary. I can then drop it. If things get sticky and I notice myself slackening, I can pick it up again no problem. A yogi can always notice the slackening and that would suffice as well, but I personally lack the diligence of mind to maintain that sort of alertness without some-sort of crutch for long periods of time, especially during sesshins.

At times, I also use the mantra to push away thoughts - "Uh, I'm thinking again! 'Alert' 'Alert' 'Alert'...Go away thoughts!" or to grasp after certain states of mind - "Oh no, I'm getting distracted and this sit's going so well - 'Alert,' 'Alert,' 'Alert.'" When this happens, and it happens easily, I just notice it happening and then become alert tothis once again. No big deal. Not like I don't try to push away certain icky states and grasp after yummy ones with everything else in my life, so why should a mantra be any different!

Setting an Intention. Like the mantra, this might sound a bit strange too - shouldn't, after all, shikantaza be objectless and intentionless! Of course, and that attitude is itself an intention!

I must admit that I learned this technique from Daniel Ingram, a Theravadan meditation master. He said that he finds it really helps him to repeat in as precise and clear a way as possible the meditation instructions before each sit. In the case of shikantaza, this would be before each activity. Repeating these instructions gives the mind some cues and enough direction, even if that direction is no-direction, so that it intuitively knows what it should and should-not be doing for the next forty or so minutes.

In my case, I repeat three times:

I vow to wholeheartedly _________ (walk, sit, weed, eat, etc) for the next ____ minutes. I vow to let each sight, each sound, each smell, each taste, each touch, and each thought come and go freely. I vow to not fall into dullness or distraction.

As with everything, we need to discern precisely what's occurring right now and respond in a wise way. It's rare that we just fall into non-discriminating alertness or remain sitting upright and alert for forty five minutes straight. Practice works more like tuning an instrument. We adjust and listen, adjust and listen, adjust and listen. In shikantaza, the adjustment is no-adjustment. We release.

Essay 2: The Basis of Shikantaza Practice and Study

When choosing any activity, it is important to understand the path, first from a rational perspective and then from an experiential one. Each path has three parts, a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning of the path is the intention, the middle is the activity or practice, and the end is the goal. The more clearly that a yogi understands and sees the path, the greater progress he can make on it, even if that path is the paradoxical path of no-path that often comes up in Zen rhetoric, one should still have a clear and thorough understanding of this.

When I speak of the "basis of shikantaza practice and study," though, it is none other than my shikantaza, my practice, my study. All those "me"s might sound a bit self-indulgent, but each of us has our own practice, our own path so our intentions, activities, and goals will always be slightly different. It helps to keep this in mind when discussing these matters, otherwise we can easily essentialize certain aspects of practice and act from self-righteousness and arrogance rather than compassion and understanding.

The intention, then, of shikantaza practice is to bring an end to our sense of separateness and the suffering which arises from that, the path is shikantaza, and the goal is wholeness. In shikantaza, we have distilled the essential urge and suffering which underpins all of our existence: the desire for wholeness, and taken that as the path. We need not look far for examples of this connection between wholeness, suffering, and our general stupidity. In marriage, for example, two people become "wedded" to one another, or joined and united. This ceremony, often seen as the penultimate expression and consummation of love through ritual, articulates that very fundamental desire for oneness sought through another. Usually, as we see in relationships and all the shit we can get into in them, we look for wholeness, sillily enough, in other things, as if they possessed it. How crazy is that! But we do it, all the time.

"You complete me." (Thanks Tom Cruise!)

"That butternut squash stew filled me up right." (Thanks momma for all your delicious food!)

"Working at Walmart pushing shopping carts in the parking lot fulfillsme." (And thanks Kyle for your awesome job!)

In all of these expressions, we see the duality which underpins it and a mind which constantly looks to these other things for that wholeness. We spend our entire lives running around looking for the perfect partner, or perfecting the one that we have through endless discussions, therapy sessions, and maybe a few holidays to someplace tropical with coconuts. We spend our whole lives going from meal to meal - "When's lunch?" "I wonder what the tenzo (Japanese for cook) will cook for breakfast this morning!" "It's already been an hour and Pizza Man still hasn't shown up yet...aghhh, I'm so hungry!" We spend our whole lives going from job to job believing that somehow this job will magically fulfill us, or at least won't be so terrible that we come home with ulsters and migraines every day.

In fact, though, wholeness is always right here. Wholeness is you reading this blog. Wholeness is you hearing the cars roll by down the gravel alley. Wholeness is you thinking longingly about your golden days as a Walmart shopping-cart boy. Wholeness is that painful joy of nostalgia. Nothing else. Nothing special. Just this. That is the basis of the practice of shikantaza. This. We are essentially whole and that this wholeness is the end of suffering and the root of compassion, wisdom, and equanimity.

Shikantaza takes as its basis faith in our essential wholeness, or the emptiness of all phenomena and experience (emptiness, or sunyata, expresses wholeness in a more negative sense). Some Mahayanies gives this faith a big name, like Buddha Nature, Self Nature, Original Face, etc. Whatever label we decide to stick on it, the practice of shikantaza, as most people understand and practice it, bases itself on faith, a faith in the mind's essential wholeness or emptiness. We can easily claim that we intuit this inherent oneness, but this doesn't get anyone very far. Some Christian will say he "intuits" the reality of God, and base his life on that intuition. A Muslim, Jew, and Hindu might all do the same thing. In this way, many Buddhists, especially those in the Mahayana traditions (Zen, Pure Land, Tibetan, Tientai, etc.), join the crowd of faith-based religions. That list alone: Christian, Muslim, Jew, and Hindu, and now Buddhist, alone should suffice for why taking faith as the path is so problematic.

Before continuing, though, the vision of emptiness expressed in Buddhism differs from these other faith-based religions in that it does not necessarily attach any metaphysical content beyond that. There is so much evidence to support it, both in the experiences recorded by mystics of other religions as well as what we know about the universe, that this "faith" is a damn good bet.

A practice based on faith, however, guides the student often from an external, metaphysical viewpoint rather than from an experiential one, even if this viewpoint is something as basic as emptiness. It takes belief as its fundamental measure and the confirmation of that belief, however lofty, as the fulfillment of it's purpose. Thus, when a Christian mystic experiences the ecstatic and ineffable presence of his God, he takes the presence of God as the definitive experience and stops there. Perhaps he will work to bring that presence into all aspects of his daily life, but he always measures it by the confirmation and fulfillment of his metaphysical beliefs. This example demonstrates only the best case.

Often, these experiences lead mystics to a state of contentment. They have witnessed God, or confirmed some lofty, metaphysical ideal through their direct perception of the Real, which, funny enough, every-one and their momma seems to claim to know, often at the exclusion of all other beliefs (I'm in this boat too, though), and then attach themselves to this experience. This experience, in that it fulfills their longing and confirms their beliefs, becomes essentialized and their progress and insight ceases there. In other words, they get "stuck" on this one view, this one experience, and it comes to dominate their life.

Now, this all gets a bit sticky because all of these mystic traditions, along with all human activity for that matter, aim at relieving suffering, although these motives usually veil themselves in elaborate metaphysical doctrines and statements of ultimate Truth or Reality. Thus, many of these far-out mystics lead happy, joyful lives content in their belief, but it might cause miscommunication and arguments between traditions about whose "experience" is authentic and also limit how one can compassionately respond because they're stuck on being "Christian" or "Buddhist." Not genuine liberation.

Through shikantaza, for example, I can verify the basis of the practice, sunyata , but how does it differ from that Hindu guru who verifies the presence of Krishna in ecstatic visions of the divine? The only way to reconcile these views is to return to their fundamental and practical basis: freedom from suffering, the beginning, or intention, of the practice of shikantaza.

Therefore, we must take suffering as the path and basis of shikantaza practice and study. This new-found basis means that before practicing shikantaza, we must first investigate the nature of suffering and then, when insight of sunyata matures, then shikantaza practice can be integrated to express that wisdom. Shikantaza with integrity, shikantaza not based on faith, requires training in traditional Theravadan Buddhist.

Essay 3: Commentary on the Bahiya Sutta

Working in the satsuma imo fields today, all I could think about was how much I hated so-and-so for being so lazy, how I was so much better than he was. Neener-neener boo-boo. I also thought a lot about how much I hated so-and-so number two, how much better I was than him, how he was a jerk and how much I wanted to tell him so. Ah, the peace of monastic life.

Thing's really get sticky when there's true silence. True silence is not the no-noise silence. In the towering pines that surround Antaiji, animals burst with sound - guttural, endless buzzings punctuated by hellish screeches or melodious warblings. At Antaiji, there is always noise, and yet out in the fields, a noiseless silence pervades. The three of us, buffoon #1, buffoon #2, and perfect me worked without a word shared between us. We were utterly alone together.

This silence arises when all the static that usually fills our lives - plans to go bowling with friends on Thursday and a Medieval Lit paper due next Monday, passes away in monastic life. Instead of the white-noise, we're face-to-face with ourselves. I don't know how this happens, but in this silence we experience and see with such intensity how and who we are.

I would like to look at these last two, the how and the who, through the lens of the Bahiya Sutta. Bahiya, the Sutta's protagonist, wears bark and lives in a hut somewhere in India. A thought pops up into his head: Am I an arahant? A deva tells him of this guy called the Buddha in Jetteva who is an Arahant and knows what's up. Bahiya rushes off to meet the Buddha and, finding him begging in the city, implores him to teach him the way to total emancipation. The Buddha says:

"Bahiya, you should train yourself thus: In reference to the seen, there will be only the seen. In reference to the heard, only the heard. In reference to the sensed, only the sensed. In reference to the cognized, only the cognized. That is how you should train yourself. When for you there will be only the seen in reference to the seen, only the heard in reference to the heard, only the sensed in reference to the sensed, only the cognized in reference to the cognized, then, Bahiya, there is no you in terms of that. When there is no you in terms of that, there is no you there. When there is no you there, you are neither here nor yonder nor between the two. This, just this, is the end of stress."

Great! So simple and direct. Just don't separate yourself from your experience. Thusness. Suchness. This. A finger. A shout. All of these are gateways to emancipation, to selfless activity, compassion, equanimity, and wisdom.

A beautiful teaching, but out in the fields today it left me helpless and stunned. How do I not separate from that jerk or that senile, lazy monk?

"It all sounded so nice and easy on paper!" I lamented as I mindlessly weeded, and then, remembering the lines, "In reference to the sensed, only the sensed," I recognized how much I lived almost completely in the "cognized." All the time sensations flow through me, something which we tangibly experience when practicing shikantaza. In fact, sensations consist of the entirety of my existence. If I stopped sensing, I would cease to exist except maybe as a floating brain somewhere in a laboratory in Norway and purely be thoughts. Simple.

Who is that jerk, really? Or that senile monk? Not to say that my "ideas" or the "cognized" is any more or less real than the sensed, I merely forgot that my experience of them includes the sensual in addition to the cognized. When that jerk speaks, it's not just words and ideas, it's also a sound. When I see him, it's not just that asshole again, it's also a play of color and light.

When practicing shikantaza, which is none other than the total expression of thusness, or the quality of wholeness and interbeing of existence, we include this aspect of our experience by remaining attentive to who we are being. In other words, we are only fully being ourselves when we include not just the cognized, but also the seen, the heard, the smelled, the tasted, and the touched, when we include the totality of our experience as it flows endlessly through us.

And then the question naturally arose, "But aren't I always being myself? Aren't I always being my experience?" In some sense, yes, I always am being my experience, what else could I ever possibly do but be it, and yet at that same time I am always rejecting or chasing after it.

This sounds similar to the same question which Dogen agonized over for years: If everyone inherently has Buddha-nature, why do they need to do anything? He concluded that practice and enlightenment are not separate. In order to fully manifest thusness and actualize our essential interbeing, we must give a wholehearted effort to be ourselves, to be not just the cognized, but also the seen, the heard, the smelled, the tasted, and the touched.

In other words, being ourselves requires incredible effort. Hakuun Yasutani, for example, described shikantaz as an activity which, when done correctly, should cause sweat to pour out of our bodies even in the frostiest of winters. Now, I don't think I should walk around sweating all the time being thusness, but there's something to what he's saying.

I can not, however, explain why we must give a wholehearted effort to be what we already are, but there's a famous Buddhist parable which might help me, and other's out there, from agonizing over this Why? like Dogen did.

The Buddha described our existence as that of someone shot with an arrow. Bummer! When you go into the emergency room with an of arrow poking out from your ass, besides the strange looks, the doctor won't ask you "How did you end up shot with an arrow in the middle of Kyoto?!" He'll ask more practical questions, "Where does it hurt? Can you feel this? Does it hurt when I do this? Can you sign this waiver? Etc., Etc."

The goal of practice should be practical, not some lofty, metaphysicaly quest - Why, if we are inherently oneness, do we believe ourselves to be separate from the trees, the sun, and that lazy monk? Why must we apply any effort at all to be what we already are?

But when we look at our experience, it does not take much convincing that we usually aren't what we are being. Usually, we are ignorant of what consists of our existence, the thoughts, sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches which comprise of our being. Through the practice of shikantaza and giving a wholehearted effort constantly within every activity, we align awareness with ourselves. We fully are ourselves being ourselves.

Essay 4: When All's Good, Practice, When All's Bad, Practice

Whenever we usually think of practice, we usually think it's only when things aren't so good. We gain insight into the impermanent nature of existence when a friend dies. We practice equanimity when, here at Antaiji, we toil in heavy rain or in sweltering heat. Ascetics, in their various forms throughout the centuries, also take this view that practice based on suffering and difficulty is the most effective. If it ain't broke don't fix it, right? Ascetics take this attitude into every situation. And by ascetics, I don't mean the bark-wearing gurus in the Himalayas-kind, although they are a kind of ascetic, I mean the kind that believes that we only practice when thing's aren't so good.

It's cold. We're hungry. We're angry at another monk because he's not helping during soji, just staring stupidly at the sunrise. "Now it's time to practice," I think, "Now I'll be equanimous and compassionate. I will not separate from the cold, or the hunger, or that stupid monk still staring at the sky. Idiot."

When the weather's temperate, our tummy's full of yummy spaghetti, and we're relaxing with a friend talking about whatever and staring happily into the noon blue, though, there's no need to practice. Things are pretty good. Not much "suffering," no big "problem" that needs fixing. Why not enjoy it?

But this type of thinking and practice is precisely the problem. We come to practice, though, with precisely this mind, to get rid of the bad stuff and hoard all of the good, and then approach our spiritual life in the same way that we've approached everything else: greedily clinging to all the pleasure, hatefully pushing away all the suffering, and being ignorant about the whole thing all the while!

At this point, though, we have a bit of wisdom. We see, however partially, that this way of living's broke and want to fix it.

If we pay attention to how we feel with a full tummy, for example, that contentment will contain within it a deep and divisive clinging. We think, whether aware of it or not, "Oh man, this spaghetti's so good and yummy! Mmm mmm! I wish I could experience this forever!" But this will not bring an end to our suffering and allow us to live in a sincerely wise and compassionate way.

Instead, it is precisely this duality: yummy spaghetti's good, growling tummy's bad, which hinders us from living wisely, compassionately, and freely. Instead of clinging or rejecting our experiences, inshikantaza we are them completely. When we do not reject our hunger, or even reject our rejection of hunger, then there is only hunger and it passes through like a cloud though the sky, unhindered and illuminated, allowed to be without being shooed away.

When we are hunger, in fact, there is no "I" to be found. Thus, being your experience through and through is the true basis of selfless activity. Being your experience through and through is the true basis of wisdom, equanimity, and compassion. What Buddha found that was so radical was that, "Hey, I can do this practice thing with any experience, both good and the bad. I can do this with yummy spaghetti and with hunger for contained in each is the duality which is the cause of all my problems." He called this teaching the Middle Way.

Thus, our practice, in order to live in a wise, equanimous, and compassionate way, does not depend on good or bad. We are always in the midst of some experience, one which we always divide into good or bad, and our path is to not separate from yummy spaghetti or a growling tummy. Our way is to not separate from any experience, good or bad. Our way is to wholeheartedly be ourselves.

When all's good, practice. When all's bad, practice.

I'd like to end with a quote from the Bahiya Sutta, named after Bahiya, one of those bark-wearing gurus, who went to Buddha while he was begging and pleaded for his teaching. After asking three times, the Buddha relented and said:

"Bahiya, you should train yourself thus: In reference to the seen, there will only be the seen. In reference to the heard, there will only be the heard. In reference to the sensed, there will only be the sensed. In reference to the cognized, there will only the cognized. That is how you should train yourself. When for you you there will be only the seen in reference to the seen, only the heard in reference to the heard, only the sensed in reference to the sensed, only the cognized in reference to the cognized, then, Bahiya, there is no you in terms of that. When there is no you in terms of that, there is no you there. When there is no you there, you are neither here nor yonder nor etween the two. This, just this, is the end of suffering."

When all's good, practice. When all's bad, practice.

[Brendan]

| <<< Previous chapter | Contents | Next chapter >>> |