| |

To you who are still dissatisfied with your zazen Translated from Japanese by Jesse Haasch and Muhô as part of the book "To you". |

To you who are still dissatisfied with your zazen

Dôgen Zenji’s practice of shikantaza is exactly what my late teacher Sawaki Kôdô Rôshi called the zazen of just sitting. So for me too, true zazen naturally means shikantaza – just sitting. That is to say that we do not practice zazen to have satori experiences, to solve a lot of koans or receive a transmission certificate. Zazen just means to sit.

On the other hand, it is a fact that even among the practitioners of the Japanese Sôtô School, which goes back to its founder Dôgen Zenji, many have had doubts about this zazen. To make their point, they quote passages like these:

I have not visited many Zen monasteries. I simply, with my master Tendo, quietly verified that the eyes are horizontal and the nose is vertical. I cannot be misled by anyone anymore. I have returned home empty-handed. [Eihei Kôroku]

I travelled in Sung China and visited Zen masters in all parts of the country, studying the five houses of Zen. Finally I met my master Nyojo on Taihaku peak, and the great matter of lifelong practice became clear. The great task of a lifetime of practice came to an end. [Shôbôgenzô Bendôwa]

So that’s why they say, “Didn’t even Dôgen Zenji say that he realized that the eyes are horizontal and the nose vertical, and that the great matter of lifelong practice became clear? What sense could there be when an ordinary person without a trace of satori just sits?”

I remember well carrying around such doubts myself. And I wasn’t the only one, a significant number of the Zen practitioners who flocked around Sawaki Rôshi abandoned the zazen of just-sitting in order to try out kenshô Zen or kôan Zen. So I understand this doubt well.

We must know that Sawaki Rôshi had a Zen master’s character – just as you might imagine it. He was also so charismatic that many, as soon as they first met him, were attracted to him like iron shavings to a magnet. So when Rôshi said, “Zazen is good for absolutely nothing” (this was Sawaki Rôshi’s expression for the zazen which is “beyond gain and beyond satori” [mushotoku-mushogo], then they thought he was just saying that. They thought that their zazen practice would at some point actually be good for something or another. I think that goes for many who practiced with Sawaki Rôshi.

Perhaps those who lived outside and who just came to the temple for zazen or for a sesshin from time to time might not have had these doubts. But those who resolved to give up their former life to become monks and practice the day-to-day, intensive zazen life in the sangha around Sawaki Rôshi, these people sooner or later began to doubt shikantaza.

The reason for this is that no matter how much you sit, you are never fully satisfied with your zazen. “Not fully satisfied” means that it does not feel the way your stomach does after a big meal. So many young people who had dedicated themselves, body and soul, to the practice of zazen began at some point to wonder if they weren’t wasting their youth with this zazen that does not fill them up at all. And many finally left, saying: “Aren’t even the older disciples, who have already been practicing this zazen for years, at bottom just ordinary people? I need satori!”

This is why many people gave up practicing. This doubt brought me almost to the breaking point as well, yet in the end I followed Sawaki Rôshi for twenty-four years until his death. So I do understand those who entertain this doubt, but I have also finally understood the meaning of the shikantaza of which Dôgen Zenji and Sawaki Rôshi speak. That is why I would now like to try to play the role of a sort of interpreter between the two standpoints.

When I say “interpreter”, that doesn’t mean only that many Zen practitioners don’t understand the words of Dôgen Zenji or Sawaki Rôshi. I also mean that although Dôgen Zenji and Sawaki Rôshi do understand the deep doubts and problems of those who try to practice shikantaza, their words don’t always reach far enough to truly soothe the root of our doubts and problems. That is why I permit myself to attempt here to present and comment on the following words of Dôgen Zenji and Sawaki Rôshi in my own way.

What does that mean in practice? Let’s take for example the passage from Dôgen Zenji’s Eihei Kôroku:

I simply, with my master Tendô Nyojô, quietly verified that the eyes are horizontal and the nose is vertical. From now on, I cannot be misled by anyone. I have returned home empty-handed.

How would it be to read it like this: “Taking this breath at this moment, I verify that I am alive.”

The reason why I can interpret it like this is because I don’t read the Shôbôgenzô as a Buddhist scholar who is only concerned with bringing order to the labyrinth of Chinese characters. Nor do I read it as a sectarian to whom every single word is so holy that he puts it on a pedestal, like a tin of canned food that will never be opened, and throw himself to the ground before it. Instead, I read it with the eyes of a person who seeks the Way, who is concerned with getting to the bottom of an entirely new way of life. And I believe that is exactly what is meant by “seeing the mind in light of the ancient teachings” or “studying the Buddha Way means studying the self.”

If we read this passage from Dôgen Zenji as an expression of our own, entirely new life, we will not get stuck in a flat and static interpretation. Instead we will realize that “the eyes are horizontal, the nose is vertical” is an expession of this fresh life we are living, breathing this breath in this moment. When we read like this, we see that Dôgen Zenji isn’t talking about some mystical state you might experience during zazen once you get “satori”. He is talking about the most obvious fact – this life right here.

That is why it is also written at the beginning of Dôgen’s Fukanzazengi, “The Way is omnipresent and complete. How can we distinguish practice from certification? The truth reveals itself by itself in every place, why make a special effort to grasp it?”

In the same spirit, what does the following passage mean? “A difference, even the breadth of a hair, separates heaven from Earth. If you make a distinction between favorable and unfavorable conditions, your mind will be lost in confusion.”

Life is this moment is fresh, raw and new. But when we think about this essential fact as an idea in our heads, we get stuck, wondering about what we can understand and what we can force into our categories. When we think about “the freshness of life”, it isn’t fresh anymore, it isn’t alive. Freshness of life means opening the hand of thought. Only when we do so can life be fresh. Zazen is this “opening this hand of thought”. It is the posture of letting go.

Now I have to say a word about the actual practice of shikantaza. Sitting in zazen does not mean that we do not have any thoughts. All kinds of arise. Yet when you follow these thoughts, it can’t be called zazen anymore. You are simply thinking in the posture of zazen. So you have to realize that right now you are practicing zazen and it is not the time for thinking. This is correcting your attitude, correcting your posture, letting the thoughts go and returning to zazen. This is called “awakening from distraction and confusion.”

Another time you might be tired. Then you have to remind yourself that you are practicing zazen right now, and it is not the time for sleeping. This is correcting your attitude, correcting your posture, really opening the eyes and returning to zazen. This is called “Awakening from dullness and fatigue.”

Zazen means awakening from distraction and confusion and from dullness and fatigue, awakening to zazen billions of times. The zazen of living out this fresh and raw life means awakening the mind, certifying through practice billions of times. This is shikantaza.

It’s said that Dôgen Zenji achieved satori through dropping off body and mind [shin jin datsu raku], but what is this dropping off body and mind really? In his Hôkyôki we read,

The abbot said: “The practice of zazen means dropping off body and mind. That means shikantaza – not burning incense, doing prostrations, nembutsu, repentance or sutra reading.”

I bowed and asked, “What is dropping off body and mind?” The abbot answered, “Dropping off body and mind is zazen. If you simply practice zazen, at that moment you are freed from the five desires and the five obstructions disappear.” (Footnote: the five desires are the desires for the objects of the five sense objects, the five obstructions are greed, anger, indolence, agitation and doubt)

So dropping off body and mind means opening the hand of thought and returning to zazen a billion times. Dropping off body and mind is not some sort of special mysterious experience.

Only this sort of zazen actualizes “the entire, unsurpassable buddha-dharma”. It is also called the “main gate to the buddha-dharma” [both expressions are from Bendôwa].

I would like to compare our life to sitting behind the wheel of an automobile. When we drive, it is dangerous to fall sleep at the wheel or to drive drunk. It is also risky to think about other things while driving or to be nervous and tense. That goes as well for sitting behind the wheel of our life. The fundamental approach to driving our life has to consist in waking up from the haze of sleepiness and drunkenness and from the distractions of thinking and nervousness.

Zazen means actually putting these basics of life into practice. That is why it can be called “seeing the whole of the buddha-dharma” or “the main gate of the buddha-dharma”. That is also the reason why Dôgen Zenji wrote “A Universal Recommendation for Zazen” [Fukanzazengi], in which he clarifies the practice of zazen.

The body and mind of the Buddha way is grasses and trees, stones and tiles, wind and rain, fire and water. Observing this and recognizing everything as the Buddha way is what is meant by awakening bodhi-mind. Take hold of emptiness and use it to build pagodas and buddhas. Scoop out the water of the valley and use it to build buddhas and pagodas. That is what it means to arouse the awakened mind of unsurpassable, complete wisdom, and what it means to repeat this one single awakening billions of times. This is practicing realization. [Shôbôgenzô Hotsumujôshin]. It would be a big mistake to interpret this as a mere warning for all not-yet-awakened Zen practitioners to not neglect their practice. The billion-fold awakening of awakened mind does not mean anything more than the living breath of vigorous life.

Some people begin with the practice of shikantaza and then give it up quickly because it does not give them that feeling of fullness or because it bores them. They do so because they only understand this awakening a billion times in their heads. That’s why they think, “Oh no! I have to awaken the mind a billion times? What I need is satori! If I hurry up and get one big satori, I can wrap up this billion-times business in a single stroke!”

It is exactly as if we were told as babies, “From now on you will have to breathe, your whole life long, this very breath, again and again, every single moment. You will breathe in and breathe out billions of times.” What baby would say, “Oh no! I’ve got to find some way to take care of these billion breaths once and for all, with one really big breath..."?

Even if we tried, we would not succeed.

That is why it continues in Hotsumujôshin further: “Some people believe that practice is indeed endless but awakening happens only once and that afterwards there is no awakening of the mind. Such a person does not hear the buddha-dharma, does not know the buddha-dharma and has never met the buddha-dharma.”

People who try to get one big satori do not accept that they must live their life with all of its freshness and vigor. Even in strictly biological terms, we can only live by taking this breath in this moment. Living means breathing this breath right now. When it is a matter of living this fresh life, it is of course not enough to simply think about your life in your head. Instead we have got to accept it as the vigorous life that it is. Only like this will we discover an attitude and posture which is fresh and vigorous.

That is what is meant by, “The great matter of lifelong practice has now come to an end.” And at the same time this is where the real practice of shikantaza begins. This is called “the unity of practice and realization” or “practice on the basis of realization”.

That is why Sawaki Rôshi always repeated, “Satori has no beginning. Practice has no end!”

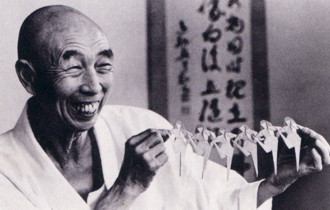

About the conditions which led to Kôdô Sawaki’s greatness

More than twenty years have gone by since the death of Sawaki Rôshi, a leading figure in the world of Zen who was active from the twenties to 1965. Even today, the immense influence that he has had on our society can be felt. Yet the conditions he was born into were unimaginably difficult and impoverished.

He was born in 1880 in Mie Prefecture. Japan was in the process of reforming itself politically and the new nation still lacked a stable foundation. In those uncertain times, when he was only four years old, his mother passed away, and when he was seven he experienced the sudden death of his father. The four brothers and sisters were divided among the families of relatives or became servants. Sawaki Rôshi, who was called Saikichi as a child, went to an uncle’s home. This uncle though also passed away a half-year later, and he was adopted by Sawaki Bunkichi, who officially operated a paper lantern business in the town of Isshinden, but in reality made his money through gambling.

This is where Saikichi spent his four years of primary school. As he started late, he did not finish until he was twelve. The boy worked as an errand boy for his step-parents. He learned about the world of gambling by selling rice cakes in the casinos and keeping an eye on the guest!s sandals. Once he witnessed how a fifty-year old man, who had hired an eighteen-year old prostitute, died from a heart attack, and how his wife came in the next morning crying, “Even in death he has to make things difficult for me – and in a place like this!”

So Saikichi as a young boy had already experienced what happens behind the curtains of our complicated world. Shortly after having finished primary school, a bloody dispute took place between roughly seventy gangsters fighting over the borders of their territories. In the evening, Saikichi’s step-father was faced with the unthankful job of establishing contact between the fleeing gangsters. Shaking with fear, he was unable to fulfill his mission. In his place, Saikichi volunteered. In the middle of the night, in a terrible rain, he crossed the scene of the bloody battle and reestablished contact between the gangsters who were already 10 km away. From that night on, his step-father began to fear him and stopped beating him.

Though Sawaki Rôshi spent his childhood years in such a milieu he also had other role models. There was the Morita family, who were scraping out a living in a run-down backhouse. The father glued calligraphy rolls while the son studied traditional Japanese painting. Saikichi felt drawn to this family, whose life, although it took place in the most impoverished conditions, had something very pure about it.

So he began to come and go at the Morita home. He studied old Chinese and Japanese history and literature from the father of the Morita family. Moreover, he learned the truth that there are things in life more important than money, position and fame. Later, Sawaki Rôshi himself said that this was how the bud formed, out of which the fruit of his later life ripened.

After finishing primary school, Saikichi took over the paper lantern business, which was how he fed his hedonistic adoptive parents (his step-mother had been a prostitute). Yet gradually he was beginning to open his eyes to his own life. He began to wonder if it was right to live his life like that and later only marry and feed a wife and children. He didn’t know up from down, but his mind clearly yearned for the way.

When he ran away for the first time, Saikichi ended up at the home of an acquaintance in Ôsaka. Yet this escape was unsuccessful: his adoptive parents picked him up again. The next time, he was determined to run so far away that no one would ever be able to catch him again.

As a 16-year old, with three kilos of rice on his shoulders and 27 Sen in his pocket, he marched with the light of a single lantern to Eihei-ji temple in Echizen, constantly chewing on the raw rice throughout the long journey. Eihei-ji could not be bothered with the runaway and Saikichi was refused entry. For two days and two nights, he waited without food or water in front of the gate in the hope that his request would be heard: “Please ordain me as a monk or let me die here before the gates of Eihei-ji.” In the end he was taken in as an assistant in Eihei-ji’s workshop. Later he helped out at Ryûun-ji, the temple of a leading priest of Eihei-ji.

At one point he had a day off and decided to do zazen in his own room. By chance, an old parishioner who helped out at the temple entered the room and bowed towards him respectfully as if he were the Buddha himself. This old woman usually just ordered him around like an errand boy, so what was it that moved her to bow towards him with such respect? This was the first time that Sawaki Rôshi realized what noble dignity was inherent in the zazen posture, and he resolved to practice zazen for the rest of his life. In his old age, Sawaki Rôshi often said that he was a man who had wasted his entire life with zazen. The point of departure for this way of life lay in this early event.

Due to various circumstances, his wish to become monk was finally granted and he was ordained in S!oshin-ji in distant Kyu!sh!u. At the age of 19, he entered Ents!u-ji in Tanba as a wandering Zen monk [unsui] but only stayed a fortnight. From there, he was sent to another temple in which he met Fueoka Ry!oun Rôshi. They understood each other well, and Sawaki resolved to follow Fueoka.

Fueoka Rôshi had studied for years under Nishiari Bokuzan Zenji, a great Zen master of the Meiji Era (1868 to 1912), and the longer they were together, the more Sawaki Rôshi was attracted to his straightforward character. Sawaki Rôshi heard lectures from Fueoka Rôshi on Gakudôyôjinshû, Eiheishingi and Zazenyôjinki, which formed the basis of his later practice of shikantaza.

Following that, Sawaki was drafted as a soldier in the Japanese-Russian War (which broke out in 1904) and earned a golden medal. At the age of 26, in the year 1906, he returned to Japan. After the war – rather late for his age – he entered the Academy for Buddhist studies in his home town. After which he transferred to the seminar of Hôryû-ji in Nara where he studied Yogacara philosophy under the abbot Saeki Jôin Sôjô.

At the age of 34, after having obtained this overview of Buddhist teaching, he began to practice zazen alone from morning until night at Jôfuku-ji, an empty temple in Nara. Here shikantaza penetrated his flesh and blood. In 1916, when he was 36, Oka Sôtan Rôshi, recruited him as a teacher for the monks in Daiji-ji in Higo. After Oka Rôshi’s death, Sawaki Rôshi lived alone on Mannichi Mountain in Kumamoto and with this as his base, he began to travel to all parts of Japan to give instruction on zazen and hold lectures. When he was 55, he was appointed professor at Komazawa University. At the same time he became godô (a head teacher) at Sôji-ji, one of the two main temples of the Sôtô school. This began the period of Sawaki Rôshi’s greatest activity.

At that time, “Zen” didn’t mean much more than the kôan Zen of the Rinzai School, but Sawaki Rôshi concentrated entirely on shikantaza as it had been taught by Dôgen Zenji. Looking at the history of Japanese Buddhism, it cannot be overlooked that Sawaki Rôshi was the first in our era to reintroduce shikantaza in its pure form and revive it as being equally valid as kôan Zen.

Because he never lived in his own temple and also did not write any books, people began to name him, “Homeless Kôdô”. Yet in 1963 he lost the strength in his legs and he had to give up traveling. He retired to Antai-ji where he died in 1965 at the age of 85.

For those who seek more information about Sawaki Rôshi’s life, there are several Japanese biographies. Here I have only brought together a few snapshots out of his life to give a rough picture to those who know nothing of him. These snapshots present the character of his adoptive step-father and the Morita family, his zazen experience in Ry!uun-ji and his encounter with Fueoka Rôshi – in short, the seed and bud out of which Sawaki Rôshi’s life blossomed.