Adult practice: Part 40

|

Our next question concerning the crossing of the legs in the lotus posture is: Why does Dogen make a distinction between left and right leg? Why does he tell us to place the left foot over the right foot, and not the other way around? Why doesn't he just say: "Lift either one foot to sit in half lotus, and lift both feet on top of the opposite thigh to sit in full lotus"? Is there a meaning in the distinction, and if there is, is it really important?

In the "introduction to Zazen" that can be found at the end of the book "Zendan", Sawaki Roshi does not go into much deatil. In a footnote, he simply states that "There are many different ways of crossing the legs. If you can not follow the fundamaental way of crossing the legs (i.e. left side up), you can cross them the opposite way as well." In a much more lenghty version of his instructions for zazen (altogether more than 100 pages), that was published in a 15 volume work about formal Soto-shu practice in 1939 and 1940 ("Zendan" came out in 1938), he explains a lot more:

"You may have some doubts about the right posture of hands and feet, as differences can be seen even in Buddha statues. I want to discuss this point here a little, so that you know the exact placement of your limbs in zazen. First you should know the difference between two ways of sitting: Gômaza, the "posture that subdues demons", and kichijôza, the "auspicious posture". Even in old texts, there is quite some confusion about the two postures. In short, the right side represents the ascending, active (yang) aspect. The left side represents the descending, passive (yin) aspect. When the right foot rests on the left thigh, that represents the ascending activity that subdues the demons (gômaza). When the left foot rests on the right thigh, that is a descending, passive activity which is auspicious (kichijôza).

You might think that this is only true for the half lotus. But that is not the case: In full lotus as well, if you first place your right foot on top of the left thigh, that is called gômaza. Gômaza also means to place the right hand first on the left foot. When the right hand is covered next with the left hand, that settles down the mind. In kichijôza on the other hand, the left foot is placed first on the right thigh (and then the right foot on the left thight) and the left hand is placed on top of the right foot, then the right hand on top of the left hand. That means that we speak of kichijôza in the case of half lotus as Dogen Zenji describes it - left foot placed on right thigh - while we speak of gômaza in the case of the full lotus (with right foot placed on left thigh first, then left foot placed on right thigh)."

Although Sawaki Roshi tries to clear up the confusion with these words, I have doubts that he is successful. It seems strange that Dogen Zenji should recommend kichijôza for half lotus and gômaza for full lotus. Sawaki Roshi does not tell us why we should sit one way in half lotus and the other way in full lotus. It is interesting but even more confusing that Sawaki also speaks about the hands. In the case of the hands, we should have them in the gômaza-posture regardless of half or full lotus - according to Dogen read in the way Sawaki does. I am afraid that Sawaki's way of reading Dogen though is not only confusing, but probably wrong altogether.

First, how are kichijôza and gômaza usually defined? The common defintion is almost contrary to the one that Sawaki Roshi uses. In the gômaza-posture, the demons (yang, right side) are subdued by the descending, pacifying activity of the (yin) left side. I.e. the left side is placed above the right side. In kichijôza it is the other way around: The right, ascending side is placed up, and this way of sitting is supposed to be auspicious. But - again contrary to Sawaki's explanations - it is important which side is on top AFTER the legs (or hands) are crossed, not which side is placed first. According to this explanation, which to my knowledge is commonly accepted in China and Japan, there is agreement with Sawaki only in the case of the full lotus posture. Both Sawaki and the common interpretation claim that Dogen describes the gômaza-posture when he writes about the foll lotus posture. But this agreement is pure coincidence, because (a) Sawaki thinks that in gômaza the right side dominates the left side, but (b) he also thinks that the foot that is raised first matters. It is almost as if you multiply "minus one" with "minus one" to return to "one".

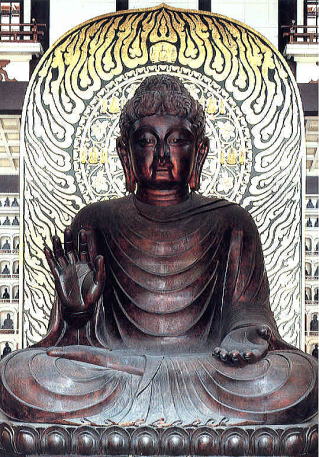

According to the common interpretation, Dogen Zenji only recommends gômaza - for both half and full lotus and for the hands as well. The reason is usually explained like this: The left side is the passive, peaceful, inward, yin, meditative side. This side is supposed to help our practice of zazen, and that is why Dogen Zenji only mentions this way of crossing the legs. Buddha statutues on the other side are often depicted with their right foot up - the way of crossing the legs that Dogen does not mention. This is explained by the fact that a Buddha has already attained complete Nirvana, i.e. there is no need for him or her to pacify the mind any more. Rather, a buddha's zazen is active, directed outward and of a yang quality, in order to save all suffering beings.

This leaves a lot of unanswered question as well: First fo all, do we really practice zazen to attain inward peace and relaxation for ourselves? Isn't it also about saving all suffering beings right from the start? If so, it would make not much sense to call the practice of a beginner "passive" or "inward" and that of a bodhisattva "active" or outward". Both have to aim at a balance of both aspects. Also, as we saw in the December issue, Indian statues always show the right side up - even when it is a statue of Shakyamuni before his enlightenment. If the common interpretation was true, we would expect Shakyamuni to sit with the left side up when he was still engaging in his ascetic practises. Some Buddha statues that originate in China though have the left side up. The one in Antaiji is one example, and the great Buddhas in Nara or Echizen (below, left and center) also depict the Buddha (in this case Vairocana) with the left foot up.

(Click to enlarge)

The common interpretation of kichijôza and gômaza can not explain these contradictions. Next time I will write about what I think is the right explanation, and what it means for the posture of the hands. Until then, I recommend that you sit which ever way makes most sense to you.

| <<< Previous chapter | Contents | Next chapter >>> |