What does it take to become a full-fledged Soto-shu priest and is it really worth the whole deal?

Part 5: Sessa-takuma – ango as life in a rock grinder

Last year I started with this series on the nitty-gritty of studying Zen in the Japanese Soto school. The question I am dealing with has two parts: “What does it take to become a full-fledged Soto-shu priest?” and “Is it really worth the whole deal?” These are two separate questions, and I am still dealing with the first. People have asked me why I am addressing these questions in the first place. One of the reasons is that many people who study Zen in the West have no knowledge of these details, and because of that often have a wrong or romantic idea of the present state of Zen in Japan. There are others who are fooled by teachers in the West who pose as “officially recognized Zen masters”, but they never explained what that recognition consists of. Another reason is that there is an on-going debate about what form Zen practice will or should take in the West, and how close or independent it should be to or from Japanese Zen. Again, this discussion is often dominated by opinions from people who do not know Japanese Zen from the inside, and therefore do not know what they are talking about. It will still take me some time before I tackle they second question (“Is it really worth the whole deal?”), but if you are in a hurry to get some input from someone who knows what he is talking about, read the papers by Jiso Forzani, the official Soto-shu so-kan in Europe. The so-kan is the director of the European Soto mission, sometimes also called the “European bishop”. Jiso is the first European to hold this job. Although he is representing Soto-shu in Europe, his ideas of Zen in Europe are very critical of the Japanese form (and the present state of European Zen as well). Have a look at his papers: From Stella del Mattino Community and The Soto Zen Connection.

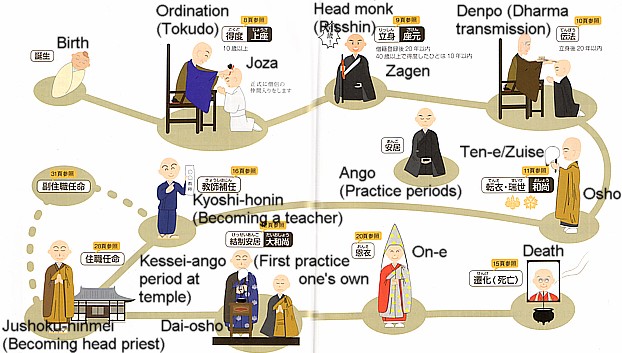

In past articles, I have spelled out some of the details in the career of a monk, often pointing to the many inconsistencies, contradictions, stupidities and ridiculous aspects that come with walking this path inside a Japanese institution. On the other side, I do not mean to make fun of most of the aspects of this path. After all, it is the path that I have been following until today and that I wish to continue to practice for the rest of my life. The next step on this path, ango, is one of those steps which I consider to be essential. The tradition of ango goes back to the days of the Buddha himself. In that time in India, monks looked for shelter during the rainy period, which lasted for three months. Ango literally means “to stay in peace” or “safe shelter”, and today in Japan it is practiced twice a year for 90 or 100 days each, usually once in the spring or early summer, then again in autumn or early winter. Dates vary from monastery to monastery, but one typical example would be April 15th through July 15th, October 15th through January 15th. In the old days, monks would travel in between the ango periods, but today in Japan monks usually get less time off (in many places, training monks are not allowed to leave the monastery over night for the whole first year). There is also a chapter in Dogen Zenji’s Shobogenzo which has the title and deals with “ango”.

If most people only do ango because of the licence, why do I still consider this step essential for a monk? Why should anyone spend time in an institution that is inhabited by 90% of temple sons with no idea of zazen or Buddhism? It is nonsense, isn’t it? Wouldn’t it make more sense to take a course on Buddhism at the university, or to simple read some good books?

The answer is that Zen practice is not something you just do on the zafu (sitting cushion), alone at your home or on the weekends in a dojo. And you certainly do not find it in books. Zen practice happens when you cook, eat or go to the toilet. For that you do not necessarily need to live in a monastery, but if you do, everything is naturally designed in a way to remind you that the 24 hours of the day are indeed practice. When you live alone at home, you have to tell yourself each time that you are indeed practicing. And more often than not, you might just be fooling yourself. If you live with a family or work with others, that is also practice, but if those that you live and work with do not share the perspective that the whole day is practice, it will be very difficult to uphold your practice during the 24 hours of the day. Sooner or later, you will just follow your idea “that everything is practice”, but that idea itself is not practice. It is just an idea.

For example, some people tell you that practice means to practice zazen for 30 minutes each morning, either alone or in a group, and that this helps you to balance your whole life. In a way, that is true. Just as masturbating every morning helps you to keep your mind of irritating fantasies during the day, and thus stay focused during school or at work. Masturbating can help to balance your hormones just as well as real sex can. But is it really the same? I do not think so. And it is certainly a different thing to masturbate each morning on the one hand, and to marry and have a family on the other side. Both things involve sexual activity. But how often you ejaculate isn’t really the question. The question is what you do with the whole rest of your life. Masturbating is easier and more convenient than living a family life. But it is just a substitute for real sexual activity, and sexual activity without the sense of responsibility and willingness to start a family – at least for me – is just something that gives kicks to your brain.

In my view, real practice as it is performed in ango is just as different from daily sitting of 30 or 60 minutes on the cushions, as family life is different from daily masturbation. Masturbating is fine. But after all, it is just masturbation. Life in a family is not so easy. That is why less and less people who have the option, opt for family life, And less and less people here in Japan opt for ango. They say it is a waste of time. And they are right, if you want to become a professional funeral manager, why go to a place like Eiheiji where no funerals are performed? If you want to use zazen as a means to balance your nervous sysytem, why bother to share your life with others that tend to rather go on your nerves?

The point of ango is: Sessa-takuma. I used this term a number of times in the past. It consists of four Chinese characters: 切磋琢磨 The first means to cut (a bone or elephant tusk), the second to rub, the third to crush (a stone or gem), the fourth to polish. As a whole, it describes how various hard materials grind each others and during this process are all refined. Interestingly, using online translation services yealds a variety of results. Babelfish has two different versions. The rather simple Japanese-English translation is “Hardwork”. When I tried the Chinese-English option, I got “Learn from each other by an exchange of views” as a result. Google translation has “Friendly competition”. Websaru has “gradual improvement by slow polishing (idiom); fig. education as a gradual process” for the Chinese term, “apply yourself diligently with everyone” for the Japanese. Ango is important exactly because it can be a pain in the ass to live with others who go on our nerves, occupy our space and demand our time, have different habits and different vies, different outlooks on life etc. They often show us a mirror because life in the monastery forces them to do so, when people in the world would just step out off our way.

What does it take to be a bodhisattva? How does a true bodhisattva practice the first Paramita, i.e. giving? By sharing one’s time, by sharing one’s space, by sharing one’s life with others. And not only with those one gets along with well, but with each and everyone whom one encounters. On the net, I read about a “zen master” who offered to become a teacher for a certain group. But only with certain conditions. First, he needs a place to live and it should not be too expensive. I can understand that. Second, he would offer zazen several times a week, but as he is a busy person, he would not attend all of the zazen himself. As this teacher emphasizes DAILY zazen, the question is: Why is the teacher himself not available every day? The answer: Among other things, he has to travel to promote his books, approximately 6 months out of each year. Books about Zen, as it turns out. Third, he would also teach “seminars” on Zen, Dogen, Sex and other things he knows about. My question: Aren’t those things to be taught in real life, through practice? Why teach them in seminars and then be away for the most part of the year? Fourth, he would take the role of the teacher. But that does not mean that he is your buddy. Rather, he wants to be something like a professor, with fixed office hours and everything. You need an appointment to see him. He is not there for you whenever you need him, because he has a life to take care of, and you are not a part of that life. Fifth, just for those who have not understood: The teacher needs his own space, distance from his students, if he lives at the center he wants his own, private entrance and everything (details here).

Living inside a monastery myself and functioning as the abbot, I think I can understand this person’s feelings quite well: I get up at 3:45 to join the community for zazen, have breakfast with them, then join samu (community work) in the morning, eat lunch with the community, work in the afternoon and sit again for two hours zazen in the evening. I have hardly a minute to spend with my family, let alone “time for myself” (but then again, I consider the whole time of the day to be “my time”). Except for the free days once every five days. So I can also get tired of people knocking on my door on a free day, telling me: “Do you have time for a little question?”, “I feel a little sick and want to rest tomorrow!”, “I need a sponsor for my visa!”, “Can you take me to the hospital?”, “I do not get along with my room-mate, can I have another room?”, “Do you have some vitamin pills?”, “The fuse broke and we have no electricity!”, “There is a guy on the phone and no-one here speaks Japanese!”, “The pressure cooker in the kitchen exploded!” etc. etc. But then again, that is the real meaning of ango. Sharing all of your time and space and energy. Does it help to balance your nerves? In my case: Not always so. But it certainly helps to mature, and in my view, practice has something to do with being an adult, developing the kind of “parental mind” that Dogen explains at the end of the Instructions for the Cook (Tenzo kyôkun): “So-called elder’s mind is the spirit of fathers and mothers. It is, for example, like a father and mother who dote on an only child: one’s thoughts of the three jewels are like their concentration on that one child. Even if they are poor or desperate, they strongly love and nurture that single child. People who are outsiders cannot understand what their state of mind is like; they can only understand it when they themselves become fathers or mothers. Without regard for their own poverty or wealth, [parents] earnestly turn their thoughts toward raising their child. Without regard for whether they themselves are cold or hot, they shade the child or cover the child. We may regard this as affectionate thinking at its most intense.”

This is the spirit of the cook in a Zen monastery, and it is the spirit that you need for ango.