Edward: When was Miyaura born?

Muho: In 1948.

Edward: What part of Japan did he grow up in?

Muho: Tokushima, on Shikoku.

Edward: Did he have a standard childhood?

Muho: Maybe for where he grew up it was kind of standard. But after the war, the first 10 years or so, Japan was poor, and he was the youngest out of seven children. Quite unusual for that time in Japan. He felt that because of the area he grew up and with so many siblings, he didn’t have the same chances if he were born in a smaller household in the city.

Miyaura went to high school but not university. It never occurred to him as an option. But it probably would have been something he could be interested in. He went to a technical high school where you learn things like welding, practical stuff. So when you graduate, you could get a job in a factory or something.

Edward: How was his relationship with his siblings?

Muho: His parents died when he was a young adult. So his older brothers were more like uncles because of the age gap. They visited here a couple of times when he was the abbot and also after he died. I remember three or four. There was also a cousin who worked for the police – he gave Miyaura a rifle, which he used to shoot the wild animals here. I didn’t see all six siblings though.

Edward: Did he have any interests when he was young?

Muho: I don’t know. In high school he played volley ball.

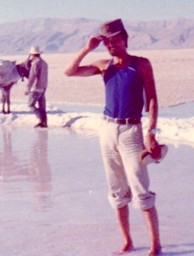

Edward: You told me before that he went travelling. What age was he when he started?

Muho: Around 20. After he graduated, he went to Kobe and worked in a cheese factory for two years until 1970. There was the hippy movement, some came to Japan. So that made him want to travel.

With the Trans-Siberian railway he went to Europe. For the longest time, he lived in London. He also lived in New York for half a year or so, working in a Japanese restaurant. He returned to London then toured through Turkey, Arabia and India. From India, he travelled to Australia, where he stayed for several months. After three or four years, he came back to Japan around 1974. Then he came to Antaiji.

Edward: How long was he in London for?

Muho: A year or more.

Edward: What was he doing there?

Muho: I couldn’t say exactly. He wrote about it in the yearbooks but some stuff is partially fictionalised. The only thing I remember him saying was that he had these Japanese friends in London who were involved in these kind of bad activities. He would help them out. I don’t know if it was drugs or what.

Edward: Was he a hippy?

Muho: To a certain degree but he was never a hardcore hippy. He never went to university, so he wasn’t a mainstream hippy. He was just curious about the world. In 1960 and 1970, the whole student movement was happening and people were coming to Japan and travelled abroad. There was news about things going on in Europe and California and he wanted to get out of Japan.

He had this woman friend from Sweden who visited one time when he was abbot. He writes about all these encounters he had with women in the yearbooks. When he came back to Japan and entered Antaiji, he was one of the few Japanese that was good with the foreigners because he could speak the language.

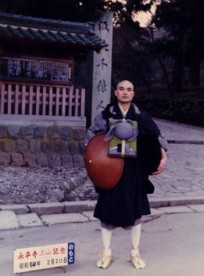

Edward: How did he first come into contact with Antaiji?

Muho: The way he always put it was, when he came back to Japan, he didn’t want to become part of the economic machine that was spinning at the time. He said, I could have got a job and retired aged 60, high up in the hierarchy with a good pension.

But he heard from somebody, I don’t know who, that if you go to a Zen monastery, you don’t need to be part of the machine. In Zen, there’s two different school. If you want to do Rinzai, go to Ryutakuji, in Shizuoka prefecture. There you have to solve koans and eventually get enlightened. Or, if you want to do Soto, go to Antaiji in Kyoto. There you just have to sit.

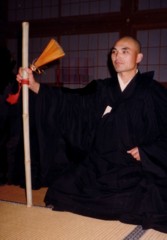

He put it like this, if I can get three meals by just sitting, then that’s what I want to do. So he went to Antaiji. And it was just at the time when the abbot changed from Uchiyama to Watanabe.

Watanabe talked to him in the hojo room in Kyoto. They had a cat named Monroe, who he was stroking in his lap. It seems then that Watanabe had the impression Miyaura wasn’t so serious – that he didn’t exactly have a connection to the Buddha dharma. So he asked him, did you ever hear of the Shobogenzo? Maybe Watanabe thought that was a question that would get him and make him think he wasn’t ready to practice at Antaiji.

But when Miyaura was living in Australia, he had gone to the Japanese culture centre in Sidney and, on the shelf, although there were not many books, they had the Shobogenzo. When Watanabe mentioned it, Miyaura said, ah yeah, I know that one.

Then Watanabe said, ok you can stay here but we’re going to move and there would be a lot of physical work. Miyaura had some knowledge about these things from high school, so he was valuable for Watanabe.